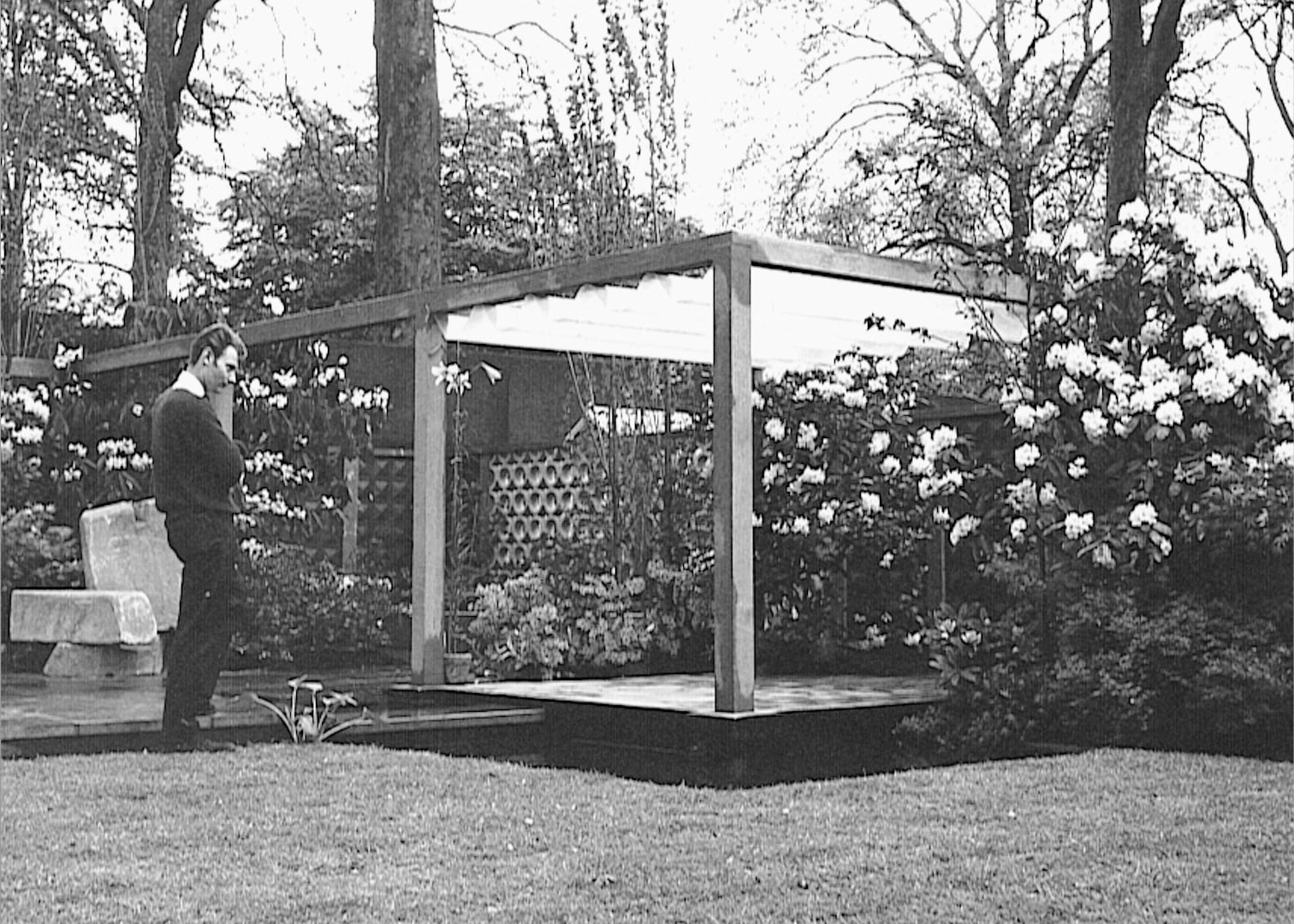

John Brookes in 1962, studying the pergola in his award-winning Chelsea Flower Show exhibition garden.

In a revealing video clip about the 1962 Chelsea Flower Show the narrator describes the event as an ‘oasis of beauty in the heart of London’, naming carnations, sweet peas, giant delphiniums, orchids, begonias, rhododendrons, azaleas, and tree peonies as those among the ‘varieties of blooms’ that were on display in the Marquee.

He emphasizes that the stated purpose of the show was ‘both educational and scientific, always striving for the perfection which Nature so abundantly offers to those who take the trouble’.

He emphasizes that the stated purpose of the show was ‘both educational and scientific, always striving for the perfection which Nature so abundantly offers to those who take the trouble’.

Among the many scenes of flowers and Princess Alexandra touring the Show, the only designed garden highlighted in the clip, described as ‘very much taking the eye was the garden of miniature roses’ created by Harry Wheatcroft ‘without whom the Chelsea Flower Show would seem incomplete’.

In contrast to today’s Chelsea Flower Shows, there were only eight exhibition gardens on Main Avenue that year. One of them was designed by John Brookes MBE. He was only 28 years old.

In contrast to today’s Chelsea Flower Shows, there were only eight exhibition gardens on Main Avenue that year. One of them was designed by John Brookes MBE. He was only 28 years old.

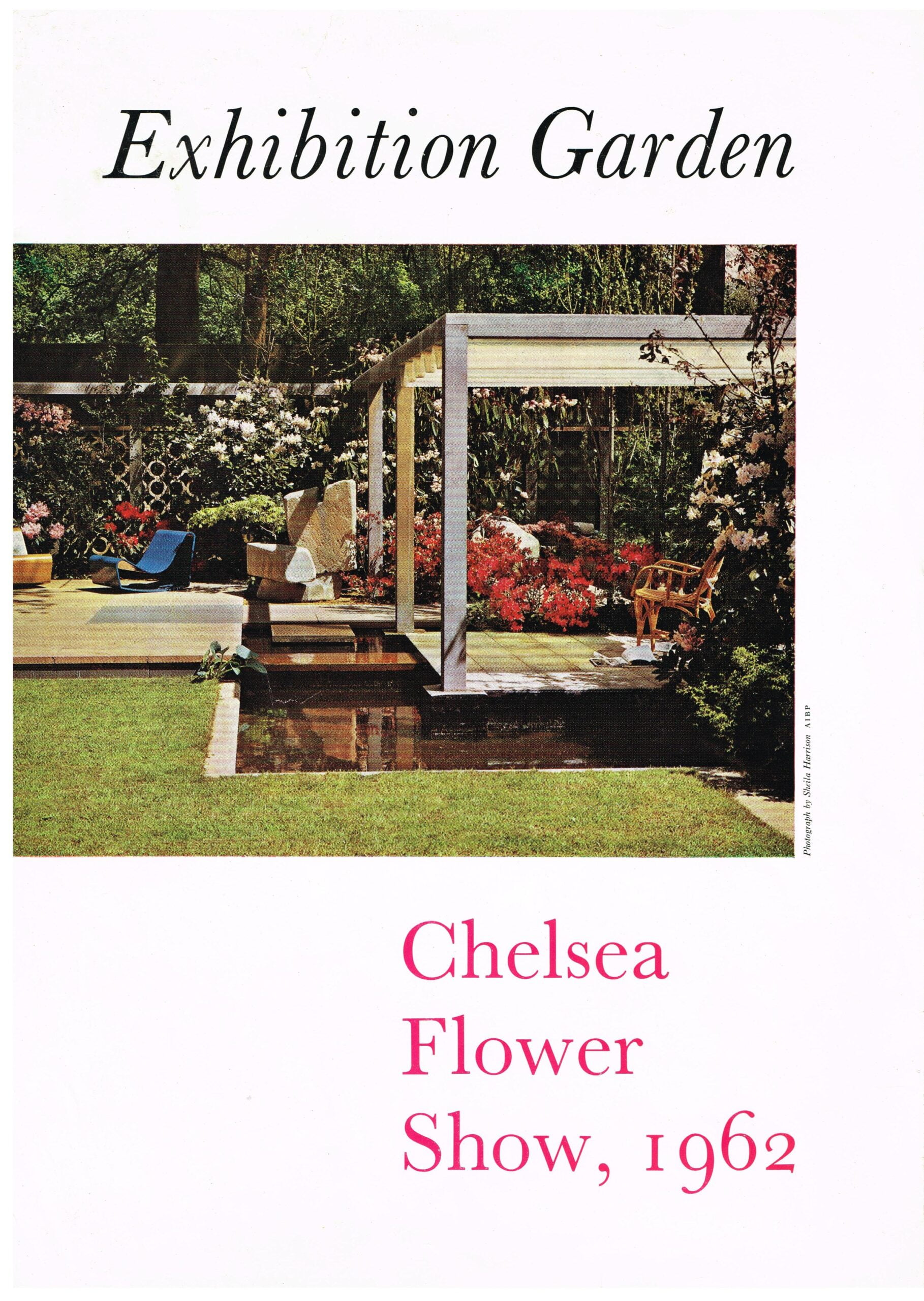

John had won a competition run by the Institute of Landscape Architects to design a Chelsea exhibition garden. Amazed he’d won, he recalled in his memoir, A Landscape Legacy (2018, Pimpernel Press), that his garden‘was remarkable because it was the first garden at Chelsea that was about design rather about merely showcasing plants. It was also the first exhibit in the history of the Chelsea Flower Show to be presented under the designer’s name rather than that of a nursery firm, as designers generally worked for nurseries at that time.’

John’s design depicted a garden for an imaginary townhouse that could be used as an extension of its indoor living space and challenged the traditional and prevailing views that a garden was all about the plants that it showcased. It was, instead, an outdoor room with multiple purposes.

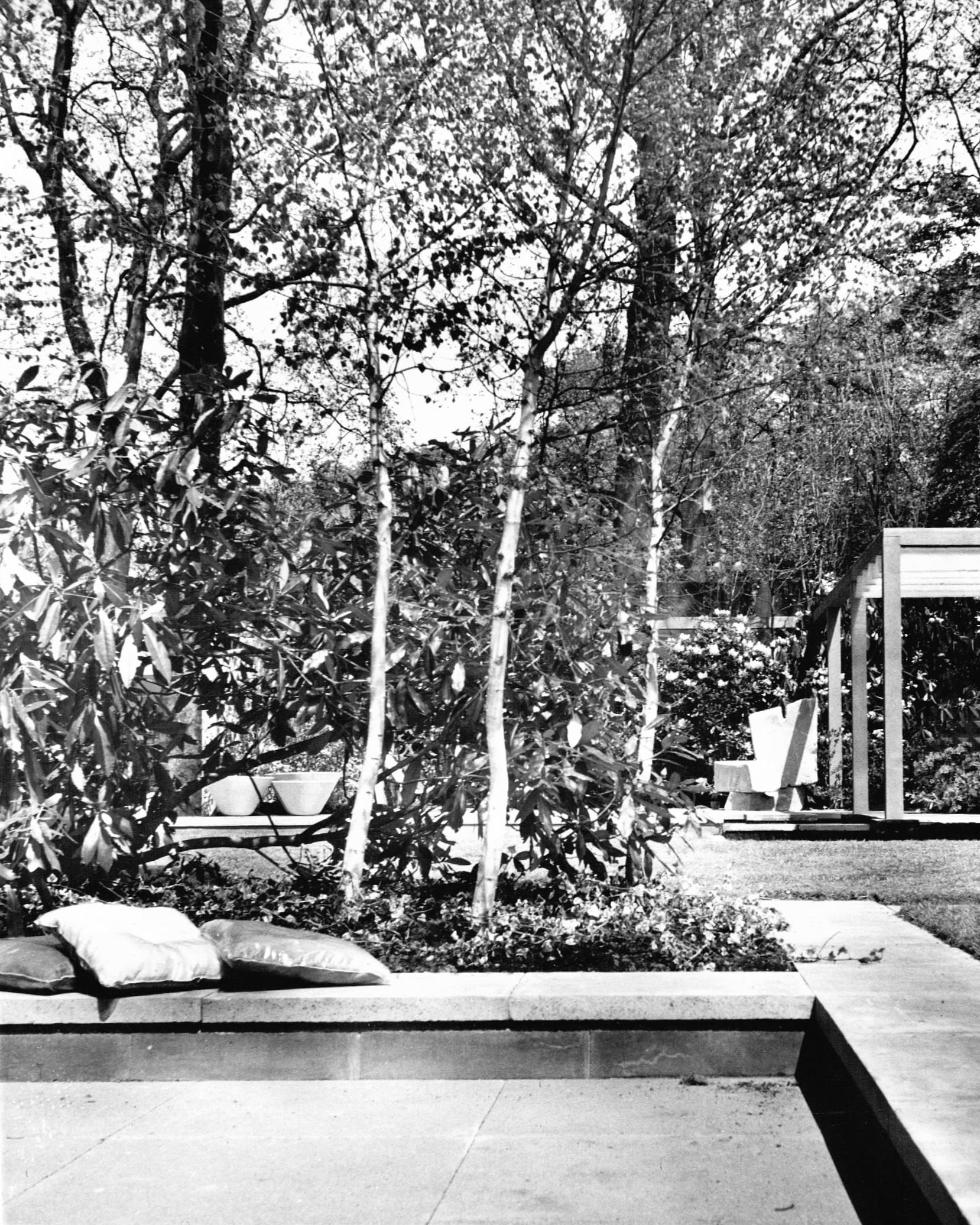

Shockingly for the time, plants were relegated to an architectural role in John’s garden. They were part of his design, but instead of showcasing individual plants, he used rhododendron, mahonia, white birch, fatsias, and pyracantha to soften his hardscape and to create 3-dimensional bulk. Meant to be low-maintenance, he accented his planting with pots and tubs filled with annuals to provide ‘bright spots of colour’.

Shockingly for the time, plants were relegated to an architectural role in John’s garden. They were part of his design, but instead of showcasing individual plants, he used rhododendron, mahonia, white birch, fatsias, and pyracantha to soften his hardscape and to create 3-dimensional bulk. Meant to be low-maintenance, he accented his planting with pots and tubs filled with annuals to provide ‘bright spots of colour’.

Believing that a garden could be much more than a horticultural display, John audaciously added modern seating, sculpture, a pergola, room for herbs, a water feature, and even an incinerator, creating a spacious and elegant ‘room outside’, a term he coined and which became the title of his equally revolutionary garden design book published in 1969 (Thames & Hudson). John’s idea was that gardens should suit the busy modern lifestyle and give its owners a place of refuge from hectic city life that was easy to manage and maintain, and within their economic means.

It is hard now to imagine that John’s concept was cutting edge but sixty years ago, the idea of a ‘room outside’ in Britain was new and few other designers, had yet cottoned onto the idea. Inspired by Brenda Colvin, for whom he’d worked in the late 1950s and who was on to the idea, as well as American designers like Thomas Church, John publicly wrote, spoke, and taught that gardens should be treated as an extension of the home, beautifully designed and linked to its interior with materials and colours. He also taught the design technique he developed called the Grid, that helped designers ensure their layouts, whether linear or curvilinear, were proportionate to the building the garden surrounded. His 1969 book, Room Outside, codified this thinking and quickly became a must-have book for garden designers and architects alike.

One of John’s sponsors in 1962 was the Cement and Concrete Association, and he used cement paving and boundary walls as well as cement structural pieces for his pergola. Concrete was a relatively new material for use in the garden, so the way John used them in his layout introduced the public to the possibility of using more affordable and modern materials in their gardens. In his memoir he humorously remembered that

One of John’s sponsors in 1962 was the Cement and Concrete Association, and he used cement paving and boundary walls as well as cement structural pieces for his pergola. Concrete was a relatively new material for use in the garden, so the way John used them in his layout introduced the public to the possibility of using more affordable and modern materials in their gardens. In his memoir he humorously remembered that

‘It would have been too costly to produce the entire garden in solid concrete for this three-day event, however, so we sprayed concrete onto the wooden frame of the pergola to simulate a concrete structure.’

Telling the story later in his life, he used to marvel that his chairs were made of asbestos – at the time its health implications, of course, were unknown.

Telling the story later in his life, he used to marvel that his chairs were made of asbestos – at the time its health implications, of course, were unknown.

In the RHS’s ‘A History of Chelsea in 10 Gardens’, John’s 1962 garden is described as ‘the garden that brought modernism to Chelsea’, and for it he won the Flora Silver medal despite its modernist and unconventional views on planting design and use of new materials.

And no wonder. It demonstrated that one could create a beautifully balanced space that combined materials, planting, and layout to create a room outside that met the demands and needs of its owners. It showed that it was possible to create a beautiful space that juxtaposed excellent design with mundane and yet essential practicality. It proposed that a garden, particularly a town garden, could serve as a peaceful refuge and living space. It encouraged homeowners and designers to explore the use of new materials and styles – if they related to the interior of the home, of course.

As we celebrate the 60th anniversary of John’s first Chelsea Exhibition Garden (one of eight he designed overall), there is a timelessness and universality to John’s 1962 garden. It is easy to imagine recreating the layout of his garden now in virtually any city in the world. The incinerator could be replaced with a composter; the concrete pergola, walls and paving with sustainable materials; and the plantings with those conducive to supporting local pollinators. The furniture would suit the style of the townhouse, both inside and out. Overall, this garden would look just as contemporary today as it did in 1962.

Most importantly, John’s revolutionary belief that a garden ‘could be a magical outside room for summer dining and an extension of indoors, lit for late evening and winter effect as well’ (How to Design a Garden, John Brookes) remains the norm.