Learning from and working with John Brookes MBE

John at work on a large estate in upstate New York.

I changed careers in the early 1990s and earned a certificate in garden design from the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG). A friend had been on John Brookes’ course at Clock House here at Denmans and recommended that I take his Masterclass in New York. I ended up taking the Masterclass in both 1993 and 1995 because it was so densely packed with information and no one else was teaching like John did at the time.

In 1998 I persuaded a client with a huge estate in upstate New York to bring John in. I knew that John was the right person to tackle the diverse 400-600 acre property. We ended up working on that project for over a decade and in the process became good friends. I was always mindful of what an amazing privilege it was to work with him.

John’s knowledge and understanding of the history of garden design and his ability to integrate historical precedent in a design while simultaneously being innovative or breaking from tradition was phenomenal. I loved how he juxtaposed structure with a relaxed planting approach. What hit me most profoundly were his drawings which he laid out on the tables on the last day of the last of his classes. They were simple black and white plans and yet were full of motion as one shape played off the next.

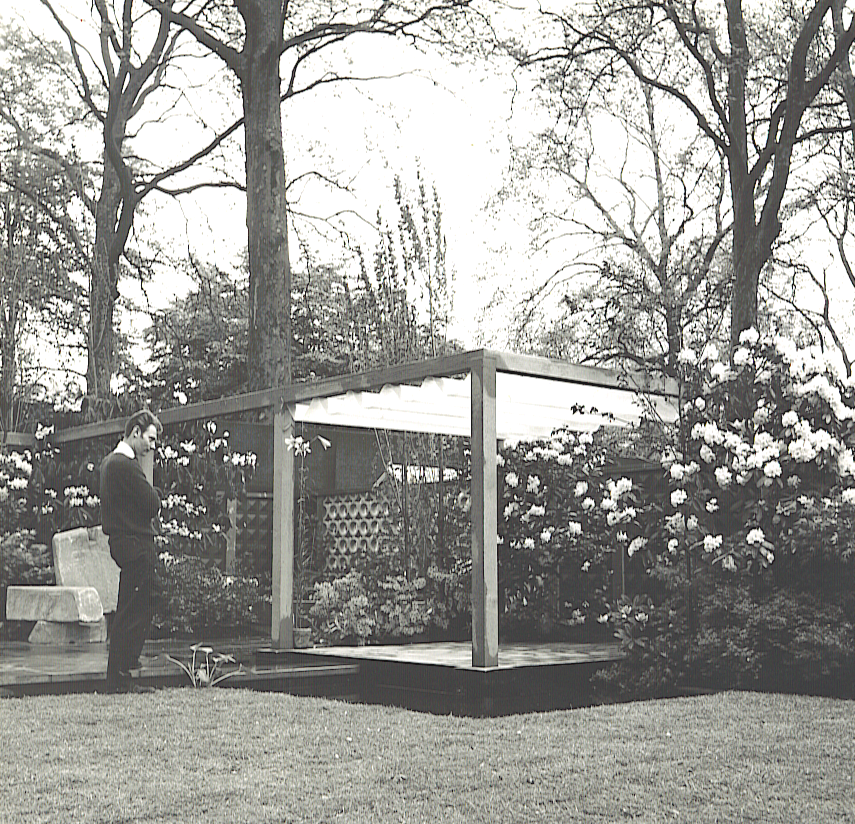

John examining his award winning Chelsea Flower Show exhibition win 1962. He was the first independent designer to show a garden and the first to show a garden that was about an outdoor living space.

It was only later when I was helping John write his memoir, A Landscape Legacy, that I learned he had been the first independent designer to show a main avenue exhibition garden at the Chelsea Flower show – it was in 1962 and he was only 29. His first book, Room Outside, was revolutionary here in Britain and the seminal go-to book for garden designers as well as architects for many years.

I had a strong understanding of John’s international work because he was always on his way to Japan or coming back from Argentina or about to go to Russia or Poland. When he came to the New York site he would share his drawings and photos with me, describing the projects and the clients and others who were involved. I didn’t realize until coming to Denmans that he was the ‘man who made the Modern garden’ here in the UK.

Editing the new collection, How to Design a Garden

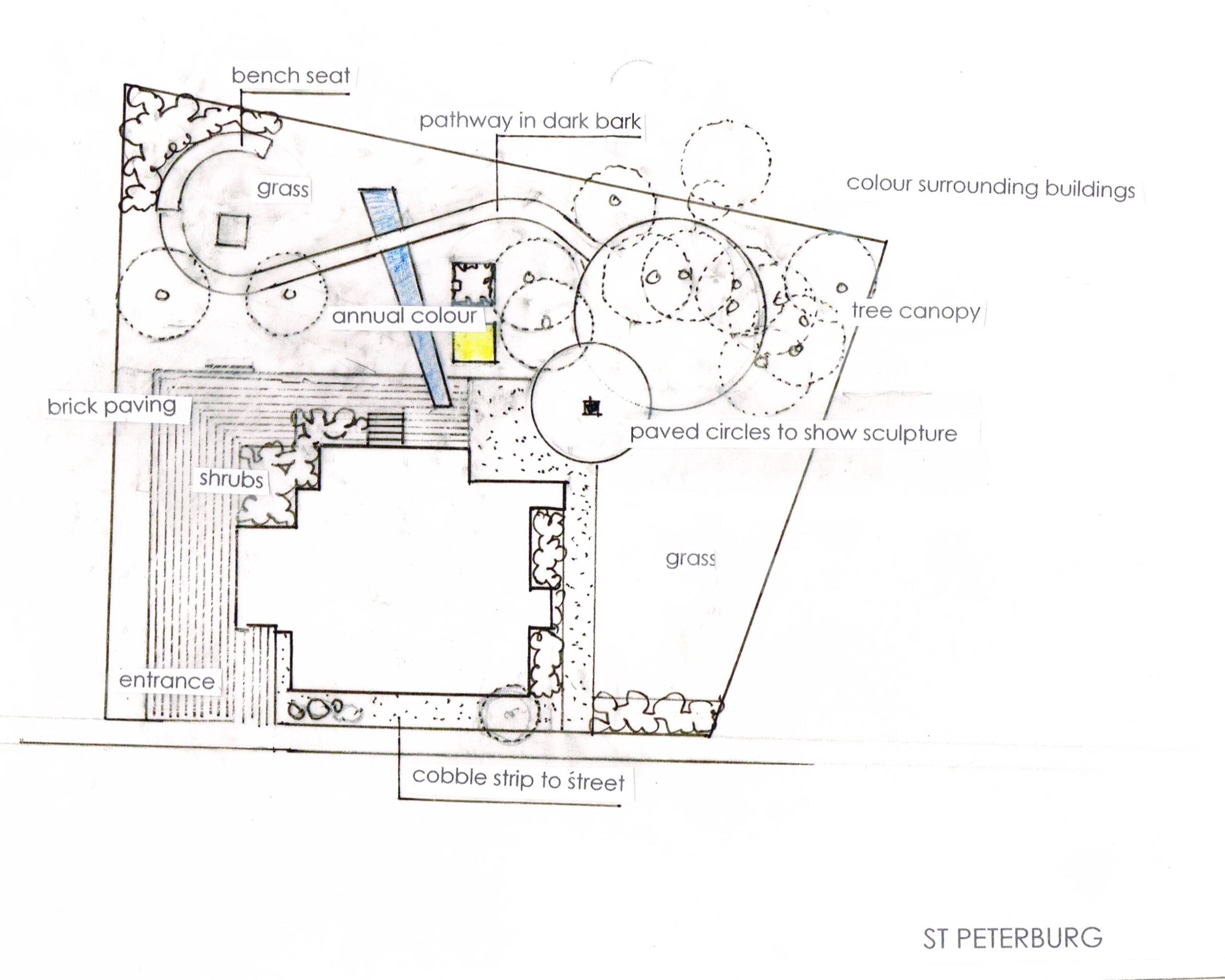

Mindful of environmental concerns,John used plants and local materials to link a garden to its setting as he did in this Russian garden.

The idea of publishing the collection of John’s writings and lectures that became How to Design a Garden started when I came across a notebook of John’s lectures from the 1990s when I was helping him write his memoir. I wanted to reread the lectures he gave when I was in his classes at the NYBG so I set them aside for a ‘rainy day’. Rainy days, as it turns out, are few and far between, but I finally managed to read a few of them during the first lockdown. The lectures he gave us were not there but several of them were very similar. They were fabulous.

Later, as we started organizing John’s papers and writings in 2019, I found there were other bits that were just as wonderful. I pulled nearly 70 pieces but was persuaded that 50 would be a nice, round number. The 50 pieces that feature in the collection were in various forms – some are lectures, some are bits John wrote for a book that was never published, some were drafts of articles, or previously published pieces. John would often wake up in the night and write down things that were floating through his head.

What motivated me to pull them into a collection was both the timelessness of John’s lessons and design philosophy, and the depth of his knowledge, experience, and critical thinking. I wanted to be sure that we included pieces reflecting John’s thinking about the environment, linking a garden to its setting, and art and the garden because they stand reading and rereading. John was concerned about conservation and sustainability issues throughout his career.

The main themes have common threads: the design process, the importance of planning, the need for communication among designer, homeowner, contractor, and even architect; the relationship between designed gardens and art; and most timely now, the relationship between garden, landscape design and the environment writ large. I learn something or am reminded about something each time I go the collection.

John was as mindful of the mundane practicalities of maintaining a garden and budget constraints as he was of the nuances of design and taught his students and clients how to balance these. The essays in How to Design a Garden reflect how he thought about the various aspects of design and how he applied his philosophy of design to his own work. He loved teaching — not just students but homeowners, contractors, other designers – and this comes across in his writing, so the pieces are all very accessible. John’s ‘voice’ permeates this book. You can almost hear him talking throughout.

The art of design

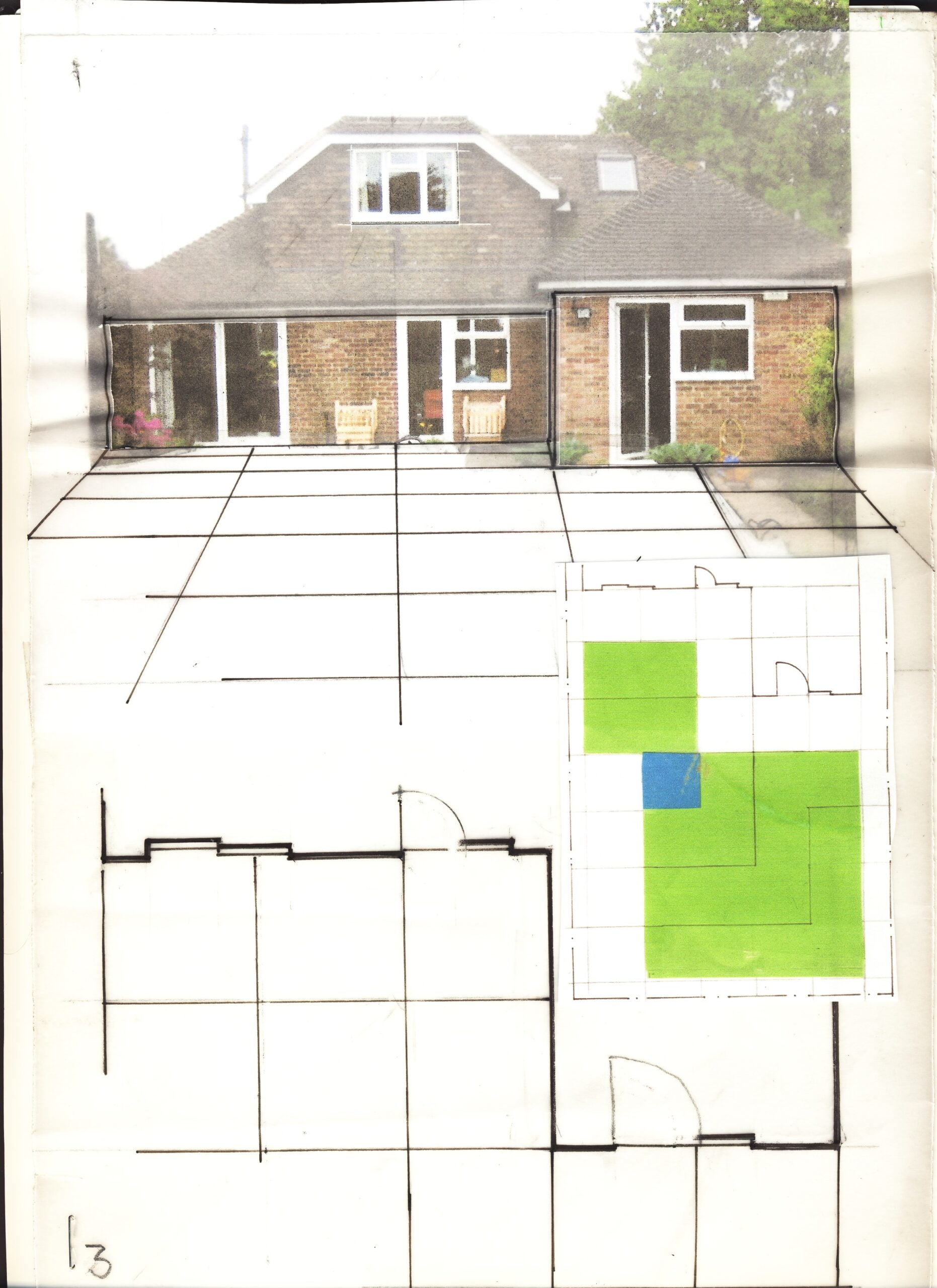

A garden plan showing the influence of 20th century abstract painting.

John began his career as a Modernist and believed that Modern art teaches us about form and mass and void and texture. Above all, it teaches us about patterns and the relationships between one shape and another. He used the paintings especially of Piet Mondrian, Ben Nicholsen, and Kazimir Malevich to introduce his students to ‘the play of shape, pattern, colour, and mass’ which is so vital to designing a good garden. At the end of the day, John said that garden design is all about the ‘relationship of shapes’. At Denmans the influence of Mondrian is especially evident in the linear lines and shapes of his garden near Clock House just outside his kitchen and studio.

Having started out as a Modernist he latterly called himself ‘contemporary’. He was influenced by the simplicity of Modernism, its use of new materials, and its clean lines but was willing to go in a more decorative direction as well.

He also gives a great explanation of how to use the lines of the garden to create a sense of movement, to keep the eye moving gently through the garden as well as, ever practical, to manage the flow of traffic through the garden. This is reflected in the layout here at Denmans where we have been working to restore the lines he laid out. There are many other subtle things that I learned whilst putting the collection together which have really helped in how I think about what we are doing to restore Denmans and its future.

Lessons

John used a grid proportionate to the features of a house to help develop his garden designs.

Anyone who reads How to Design a Garden will find John’s four basic lessons in designing a garden, which include his famous Grid methodology. He used the Grid to ensure that the proportions of a garden work with those of the house.

The book lays out John’s tips on learning ‘to look’ both at a landscape and at art. So often John’s former students will emphasize that this is one of the most important skills they learned from him. It is just as important for homeowners as it is for designers to learn to observe what is around the site they are working on so they can infer the best plants, materials, siting, and other components of design so it sits comfortably in a landscape.

The art of horticulture

How to Design a Garden talks extensively about how to think about planting design. John always used to say plants come last in a design, just like the accessories in interior design, but he also talks about how to think about the role plants play in a design. The book lays out his approach to choosing plants and why – and some of his pet peeves.

John explains that understanding the climate and soil site, as well as its cultural nuances helps to ensure that a garden will ultimately feel at home in its setting. Those working with small gardens have as much to learn as those with larger sites – from practical tips to pure design techniques.

It is worth reading John’s views on sustainability, biodiversity, and even cultural diversity. He thought broadly about these things and his travels enriched his perspective tremendously. This comes through strongly in his writing.

So does his extraordinary sense of style. His views on style (and what is NOT style) are reflected in several of the pieces. John proved that a balance can be struck between mundane practicalities and beauty if one only takes the time to plan and assess a site, a valuable lesson for us all.

John’s design philosophy applies around the world. Pampa Infinita is a design school he set up and that is still thriving.

And it is brilliant that the advice he gives to his Argentine audience is as applicable to his Japanese audience and vice versa – as well as his American audience, British audience, etc. etc.

I believe that How to Design a Garden will appeal to anyone who is interesting in gardening and design, including the relationship between architecture and the landscape. Designers, and students of design can learn from how he worked with homeowners and homeowners have much to learn from his advice to designers. A mutual understanding will necessarily help facilitate communication between the two.

Landscape and the local ‘vernacular’

John had such a broad set of experiences going into his career and built on them throughout his lifetime. From working on farms as a lad (he wanted to be a farmer) to walking his dogs in the countryside to working in the Nottingham Parks Department, he developed a deep, fundamental understanding of the land – both its makeup, including soil and geology, and its topography.

From the time he read Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in the early 1960s, he became increasingly sensitive to environmental issues that we would call sustainability or biodiversity today, and he integrated those concerns into his lessons everywhere he went. He taught us to work with our locations rather than against them; with nature rather than against it. As he said, ‘We have to do our own thing by learning to read our own landscapes, and its plant associations. A weed is only a plant in the wrong place; it’s a native otherwise.”

John used the jagged lines of these terraces to link this Patagonia garden to the Andes beyond.

And he placed enormous value on linking a garden to the local vernacular and culture. He deplored the tendency for sameness in design and that comes through in the book. We ran a small exhibition at Denmans in 2019 called ‘The Garden in its Setting’ – a phrase John used – that featured four gorgeous gardens John did abroad. One was in Poland, another in Russia, the third in Argentina, and the fourth in New York State. Each is in a completely different setting, and each garden, therefore is different. Perhaps the most striking example was the garden in Patagonia where he used strong, angular lines in the terraces he created between the house and lake to reflect the strong angular lines of the Andes in the distance. His plantings were similarly bold and simple. Stunning.

John believed that ‘by planting in a softer, more natural way one can achieve a more maintenance-free, more relaxed and more conservation aware garden that sits comfortably within its setting’ but he always emphasized that the starting point is good design and good structure.

Rather than starting with plantings he started with a garden’s structure and then reinforced his designs in the third dimension using architectural plantings. All the while, he was working within the constraints of the environment and climate he was designing. As he said, ‘go with the lie of your land and you will make life easy. Fight it and it’s double the work’.

Looking ahead

John wrote at least 25 books about design so you might think that is enough, but I believe this book is different. It is broader and I think an excellent companion to any of the design books; a ‘portable Brookes’ if you will. Rakesprogess reviewed the book in September 2021and said ‘Practical, insightful and innovative, Brookes’ reflections as set down in this anthology are enduringly sharp – an essential book to have in your garden library’.

John’s own planting style is evident at Denmans, his home and garden in West Sussex for over 38 years.

How to Design a Garden is definitely not a retrospective. John was always appalled when people asked him to talk about his past projects. He wanted to talk about what was happening now and what lay ahead. He could be quite sharp about this.

Ultimately, I hope this book will provoke discussion and thought among horticulturalists, designers, architects, contractors, and homeowners, all of whom should gain from reading it.

For more information, please contact Louise Campbell

louise@denmans.org 07540892364

@denmans_garden