A brilliant plantswoman, Joyce Robinson travelled to Greece in 1969 for a transformative month’s holiday.

She was captivated by the rampant plants and climbers which grew abundantly on the island of Delos and the way they cascaded “over and through ancient urns and pillars, down deep wells and water holes, covering steps and the stairs to homes long forgotten.” She loved it so much, she was the last person on the boat when it was time to weigh anchor.

By the time she returned to Denmans where she had been living, gardening, and farming since 1946, Mrs. Robinson was determined to incorporate gravel into her garden’s design. Gravel was a little used medium in gardens in the 1960s and 70s, but she was convinced it would be an exciting alternative to lawn and paving.

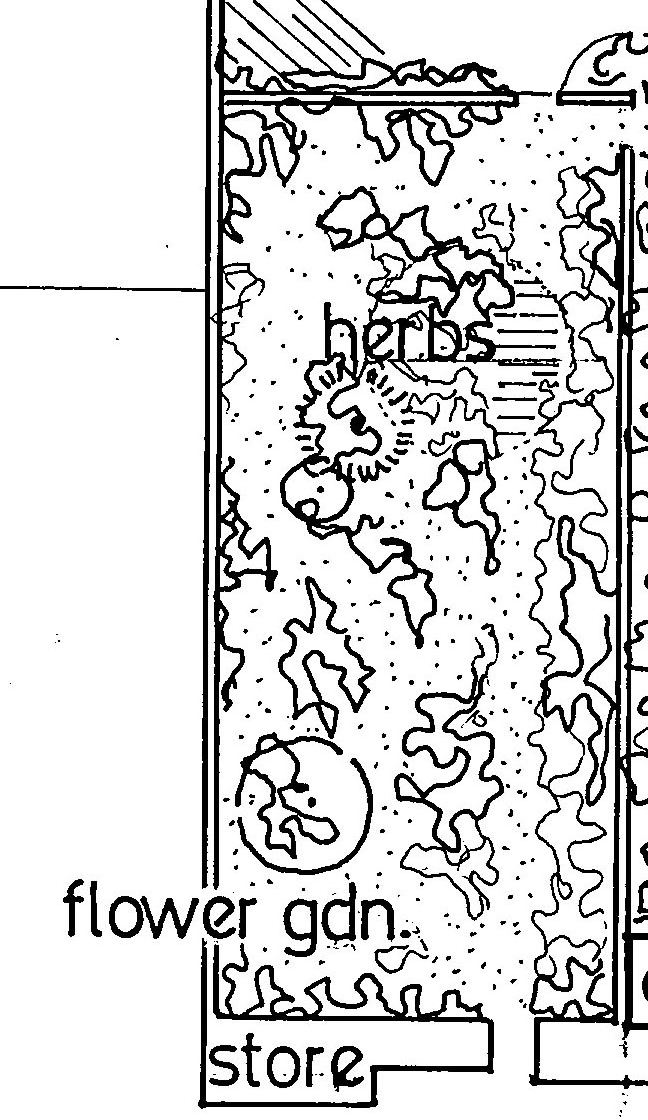

Mrs. Robinson’s first gravel garden was in the Walled Garden where she had been growing veg for the Covent Garden Market since the late 1940’s.

A year later, she retired from farming and began her experiment. Her laboratory was the Walled Garden in which she’d grown veg for the Covent Garden market for years.

Rejecting gravel that “has been graded and cut by machine” she settled for local gravel dredged from the harbour at Littlehampton. It was of a colour and texture that worked well with the brick and flint walls at Denmans.

Ploughing under vegetable beds, Mrs. Robinson festooned the walls with unusual climbers and roses, many of which still flourish here. Knowing she didn’t have enough time to maintain a “conventional, patterned herb garden”, she let her plants self-sow and ramble, pulling the ones she didn’t want and nurturing the rest. Selecting plants that varied in height and bloom time, she achieved the naturalistic effect she was aiming for.

Photo credit: Philip Pilcher Mrs. Robinson’s approach to the second gravel garden was more about removing plants the remaining ones could be enjoyed up close.

In 1972, encouraged by the result, Mrs. JH continued the experiment on the other side of the garden in her shrubberies, removing selected shrubs and trees and spreading gravel around the rest so visitors could walk freely among the plantings which included the tree peonies, euonymous, weigela, and flowering cherry trees that still exist. The gravel eventually extended from the old Victorian conservatory, in front of her cottage, to the other side of the garden. She was pleased with the look and also that she could walk “dry shod” through her garden on damp days.

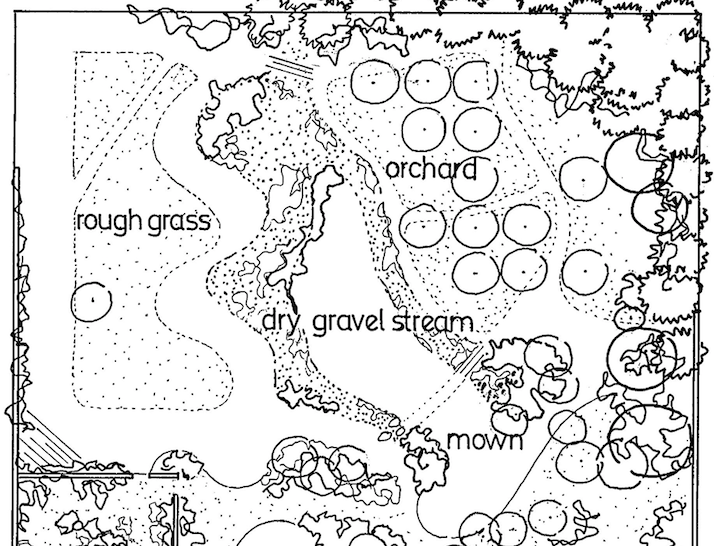

This plan of the Garden, (c 1978) depicts Mrs. Robinson’s new riverbeds.

In 1977 Mrs. JH sold her Guernsey cows, freeing up a one-acre calf paddock just south of her lawn. The site sloped gently down, giving her views of the tree lines beyond. She wrote. “I walked by it by day and by night, and planned so many different gardens and enchantments on that piece of ground. The idea came quite suddenly. Why not gravel streams or river beds?”

Mrs. Robinson’s riverbeds were more land art than border.

Her inspiration again came from nature, but this time from nature closer to home — from the winterbourne rivers of the South Downs that go dry in summer.

At the age of 76 she climbed onto a tractor to start her new gravel experiment. More land art than garden bed, Mrs. Robinson created two faux riverbeds that “flowed” down the slope and terminated in a dry water hole. It was a three-year project. She painstakingly arranged different grades of pebbles and cobbles in a naturalistic way, using stone from the River Rother to enhance the effect. As she didn’t wish “to repeat early patterns of planting, an imaginary dry stream or watercourse was described with rocks and gravel, grasses, willows, and plants…”

Landscape designer John Brookes MBE visited Denmans in 1973 and fell in love with its originality, relaxed peacefulness, and how Mrs. Robinson worked “with rather than against, the limitations of the location”. Her brilliant naturalistic plantings and plant associations delighted him. And that Denmans wasn’t steeped in past gardening traditions that were high-maintenance, restrictive, and pretentious appealed to him, too.

John had been using gravel as an alternative to grass since the 1960s in posh London gardens.

John had been experimenting with gravel in posh London gardens where grass grew poorly, and modern lifestyles limited the ability of his clients to tend their gardens. Having introduced the British gardening public to the notion that a garden could be used as an extension of their homes as a “room outside” (the name of his first design book published in 1969), he advocated using materials and plants in a way that was low-maintenance and practical but attractive.

He felt that Mrs. Robinson was doing something similar, writing that she “was using gravel innovatively at Denmans at the same time that I was using it for more practical reasons in town gardens in London. Back then, using gravel as part of a garden’s design was still very new”.

John loved Denman’s relaxed style and innovative approach to gravel and planting.

Denmans, he concluded, was “an interesting garden, for it was planned with a continuity of growing surprises which poked their unexpected way through its surface to create at all times a jungled profusion of texture and form as well as colour”.

John visited Denmans again in 1979 after returning from two years in Tehran, where he had established a school of interior design for the Inchbald School of Design, and India, where he conducted research for his book, Gardens of Paradise. By this time Mrs. Robinson was looking for someone to take over the garden’s management and John was looking for a place to start his own garden design school.

Unlike the rest of the layout of Denmans, the garden outside Clock House, his new home was reminiscent of Piet Mondrian’s paintings.

With Mrs. Robinson’s blessing, he renovated the stable block to live and teach in, named it “Clock House”, and began taking over the management of the garden. He also created his own garden and terrace just off his kitchen. There he used strong shapes and lines reminiscent of Piet Mondrian and planted Mediterranean shrubs, trees and perennials. He finished off his space with a pergola reminiscent of those he’d incorporated in gardens in London.

Over the next several years, while running the Clock House School of Design and beginning to design abroad, John revised Denmans’ beds and walks, creating garden rooms and spaces that embraced Mrs. Robinson’s gravel gardens. When a circular pond was built in front of her cottage in 1982, he integrated it into the gravel garden that swept from the wall on Denmans Lane across to her Victorian conservatory, with bold, simple, curves. Interestingly, while his own garden was a series of squares, rectangles, and straight lines, in the rest of the garden he used curves reminiscent of Roberto Burle-Marx, the Brazilian landscape designer whose work John greatly admired.

The Daydreamer, by Marian Smith, contemplates reflections and the changes of the seasons.

In 1984 John replaced the dry water hole at the bottom of the dry riverbeds with a pond with Anthony Archer-Wills that added sparkling light and attracted wildlife. The Marian Smith statue of a boy he placed at its edge still sits contemplating pairing ducks, and water lilies in a perpetual day-dream.

Mrs. JH passed away in 1996, and John continued living at Denmans adding his own elements and touches until 2018. He gave the garden “a continuity as one walked round, and a sense of moving through from area to area”. He took into account her plantings as he reshaped beds and areas of rough and mown grass, playing “shape against shape”, and he added some of his favourite plants as some of Mrs. Robinson’s died out.

Denmans is a complex medley of horticultural beauty and strong architectural plantings.

Though 2020 marks “Fifty years of gravel gardening at Denmans”, Denmans is not just a gravel garden. Here gravel gardens merge seamlessly with mixed borders, woodland and shrubbery, as gravel walks merge seamlessly with paved and grass paths, making the property feel larger than it is and amplifying its tranquility.

Mrs. Robinson’s naturalistic plantings, plant associations, and ground-breaking use of gravel still meld harmoniously with John’s sweeping lines, strong architectural plant combinations, and play of mass against void and bold shape against bold shape.

Repetition of line, shape, and plant material lends the garden coherence; plants from around the world delight visitors, pieces of sculpture serve as focal points, and topiaries of oversized chickens provide whimsy.

John distinguished between “designers” and “plantspeople”. He was the former and Joyce was the latter. It is their common sense of place, rooted squarely at the foot of the South Downs, where the two come together, providing the perfect setting to fuse their passion and vision. Both saw the garden with a painter’s eye and were uncompromising about the importance of structure, form, texture. Both were fundamentally practical and unpretentious, concerned with maintenance requirements, ecology, and the sustainability of their garden. Neither was fettered by convention.

The Walled Garden remains enchanting, as beautiful in summer as it is in winter.

The Walled Garden, where Mrs. JH began her gravel experiment, remains an ebullient blend of plantings. The brick and flint walls still bear her roses, clematis, Vitex, and other vines, and many of the unusual shrubs she planted remain in place. John’s layout is a powerful combination of natural organic shapes juxtaposed upon strong geometric shapes softened by plantings and materials.

Mrs. JH described Denmans as “glorious disarray’, the title of her 1989 book, which evolved into what John affectionately referred to as “controlled disarray” under his eye. As John once said, it is “a type of decorative gardening from which we all can learn.

This Autumn we are beginning a painstaking restoration of the gravel gardens that will take some years to complete. One area of focus is outside of Clock House, where the Mondrian-inspired garden outside of Clock House has been overgrown. It will include the rebuilding of the iconic pergola he had in his original design.

The garden in front of the cottage as it was the day of Mrs. Robinson’s funeral in the summer of 1996.

The other area is just south of the Cottage where John started to revise the gravel garden around the circular pond in 2018, re-laying the border after having had it almost completely cleared. Unfortunately, he died before he could begin to replant, and he left no indication of his intentions. We replanted it with shrubs and perennials that worked with the colours around it temporarily, but it is time to restore it. We know where the old lines of the border were, but the planting of this area will be guided mostly by old photos from before Mrs. Robinson’s passing in 1996 and the plantings that John left in place, especially a splendid red Japanese acer she planted in the early 1980s. While we hope that the Clock House project will be finished in 2021, the project in front of the Cottage will take two years to finish.

And meanwhile, we will continue the ongoing restoration and maintenance work in the rest of the garden!